From Harlem to Oyotunji: The Black Gods Who Birthed a Nation

- Lauren McCaskill

- Dec 4, 2025

- 3 min read

Tracing how Yoruba revivalism migrated through Garveyism, the Nation of Islam, and Pan-Africanist circles to create a blueprint for liberation.

In the afterglow of the Harlem Renaissance, when jazz and politics pulsed through uptown

streets, something older was stirring beneath the surface—an ancestral rhythm, a call that carried the memory of kingdoms and gods across the Atlantic. Harlem was not just a stage for poets and revolutionaries; it was a portal. From its tenements and storefront temples, a new form of Black nationalism took root—one that found its heartbeat in the cosmologies of Africa.

The earliest sparks were lit by Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement

Association (UNIA), whose headquarters on West 135th Street made Harlem the capital of a

global Black awakening. Garvey preached self-reliance, race pride, and a return to the mother

continent. His parades of red, black, and green uniforms were processions of rebirth, turning

colonial shame into sacred procession. Beneath the pageantry lay a deeper current—Garvey’s

call for sovereignty was not only political but spiritual. He insisted that liberation required more than new laws; it demanded a restored identity, a remembrance of who we had been before the ships.

That spiritual current ran forward into the 1930s and 1940s through the Moorish Science Temple and later the Nation of Islam (NOI). Both inherited Garvey’s message and re-clothed it in sacred language. Elijah Muhammad’s “Do for Self” echoed Garvey’s “Race First.” In the temples of Harlem and Chicago, the Black body was reimagined as divine, and the streets became sanctuaries. This was not simply religion—it was a theology of sovereignty. The Nation of Islam, like Garvey’s movement before it, understood that freedom begins in the imagination; to name oneself anew is the first act of independence.

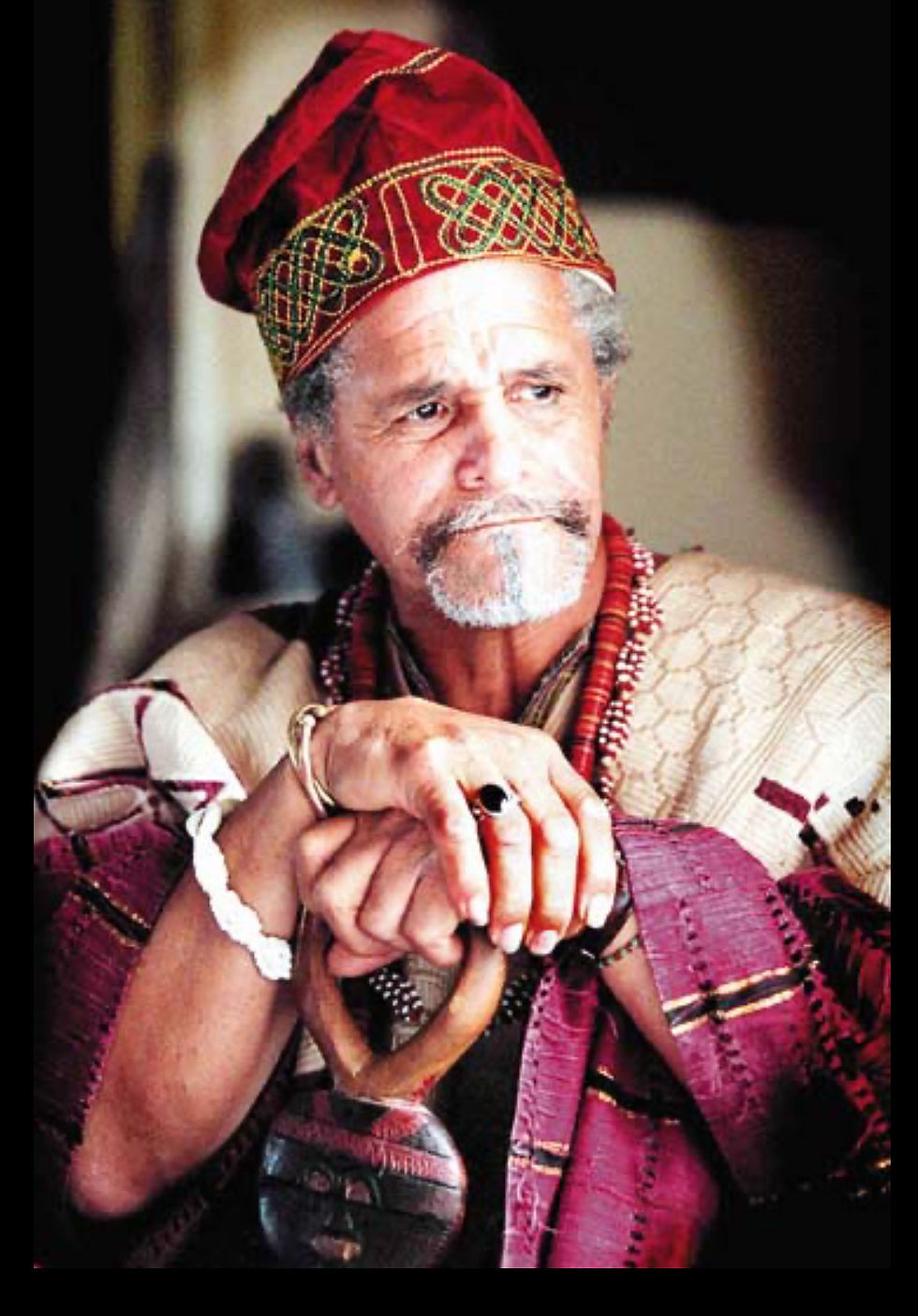

Out of that same soil emerged the Orisha-Vodun revival, carried by priests, artists, and activists who refused to believe that Africa was a metaphor. Among them was Oba Efuntola Oseijeman Adefunmi I—born Walter Eugene King—a young artist from Detroit who found his way to Harlem in the 1950s. There, amid the swirl of Pan-African meetings and jazz clubs, he

encountered the remnants of Garvey’s followers, the oratory of Malcolm X, and the quiet

persistence of African traditional religion kept alive by Caribbean elders. Adefunmi saw in the

Yoruba cosmology not only gods, but governance: a model for nationhood grounded in balance, discipline, and ancestral law.

By the late 1950s, he had founded the Shango Temple in Harlem—one of the first Orisha

temples in the United States. It was a modest room adorned with cowrie shells and drums, yet its purpose was revolutionary. The temple wove together Garvey’s nationalism, the Nation of Islam’s self-definition, and the Yoruba vision of divine order. In ritual, Adefunmi and his

followers enacted what Garvey had preached and Elijah Muhammad had prophesied: a people governing themselves through sacred law.

In 1970, Adefunmi carried that vision south to the lowcountry of South Carolina, where he

founded Oyotunji African Village—literally, “Oyo rises again.” Set among the moss-draped oaks of the Sea Islands, Oyotunji declared itself a Yoruba nation on American soil. Its founding

document proclaimed, “We reclaim our right to sovereignty, guided by the ancestors and the

Orisha.” The community built shrines, held coronations, and established ministries of culture,

agriculture, and education. It was both a sanctuary and a statement: that African Americans could be a people unto themselves, governed by ancestral wisdom rather than the logic of oppression.

The creation of Oyotunji was not an isolated act of utopian imagination. It was the living

continuation of a Harlem-born lineage that stretched back to Garvey’s parades and the prayer

circles of the Nation of Islam. Each movement carried the same question in different

tongues—what does it mean to be free when freedom has been denied for centuries? For

Adefunmi, the answer lay not in assimilation but in reclamation. By restoring Yoruba rites,

language, and governance, he sought to rebuild the psychic architecture of a people fractured by the Middle Passage.

Today, more than half a century later, the echoes of that work endure. From Brooklyn’s Orisha

temples to Pan-African festivals in the South, the spirit of Oyotunji continues to remind us that

liberation is not a metaphor—it is a practice. The drums that once called the faithful to Harlem’s storefront shrines now resound across the diaspora, summoning a generation to remember the gods who birthed a nation. In tracing the path from Harlem to Oyotunji, we see that the geography of freedom is spiritual as much as political. It begins wherever Black people dare to remember that they are the descendants of kings and priestesses, not property. Harlem gave the movement its fire; the Nation of Islam gave it form; Oyotunji gave it flesh. Together, they chart a blueprint for liberation that is as ancient as the Orisha and as immediate as the present struggle—a reminder that every act of remembrance is also an act of revolution.

Comments