Black Ballet: From Erasure to Center Stage- Selina Gellizeau

- Selina Gellizeau

- Feb 3

- 5 min read

The hidden Black lineage of ballet, from pioneers denied stages to today’s artists

reshaping the form

Ballet often presents itself as universal. Grace without borders. Beauty without bias. A language of discipline and devotion that promises access to anyone willing to work hard enough.

But ballet has never been neutral.

Behind the soft lighting and silk ribbons lies a long history of decisions about who belongs onstage, which bodies are celebrated without explanation, and who must justify their presence simply to be seen. Black ballet did not arrive as a disruption of tradition. It existed all along, cultivated through genuine interest and undeniable talent, even as Black dancers were intentionally excluded from representing the art form they helped sustain.

Ballet’s Anti-Black Origins in White History

Ballet developed within the courts of Renaissance Europe, first in Italy and later formalized in France under royal patronage. It was crafted to reflect social hierarchy, refinement, and proximity to power. Though framed as art, ballet also functioned as cultural signaling.

As the form professionalized, white European bodies became the visual reference point for technique, proportion, and harmony. Their features shaped what was considered correct, elegant, and refined.

This is how whiteness became the baseline.

Pink tights were labeled neutral. Pointe shoes matched one skin tone with limited variation. Hair and makeup standards favored straight textures and restraint. Romantic leads reflected white ideals of femininity that rarely included Black women. These were not incidental preferences. They were structural choices that shaped who felt welcomed and who was quietly discouraged from participating at all.

Barriers Before the Stage

For Black dancers, exclusion often began early.

In North America, segregation restricted access to elite ballet schools, feeder programs, and professional networks. Many Black children were never offered the opportunity to train classically. Those who were often found themselves isolated as the only Black student in the room.

Even undeniable talent did not guarantee acceptance. Some dancers were encouraged to alter their appearance to blend in. Others were redirected toward styles deemed more appropriate for their bodies or skin tone. Touring dancers faced dangers their peers never had to consider, navigating segregated towns where applause offered no protection once the curtain closed.

Black dancers were expected to embody excellence, composure, and gratitude at all times, as though their presence were provisional. White dancers were afforded the freedom of focusing solely on craft.

Black Pioneers Who Refused to Disappear

In the 1940s, Janet Collins was offered a contract with Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo under the condition that she paint her skin white. She refused. In 1951, she became the first Black ballerina to perform at the Metropolitan Opera, choosing integrity over access in a moment that still resonates through ballet history.

In 1955, Raven Wilkinson joined Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, performing classical roles while navigating the dangers of Jim Crow America. Her career revealed a sobering truth. Inclusion did not ensure safety, dignity, or respect.

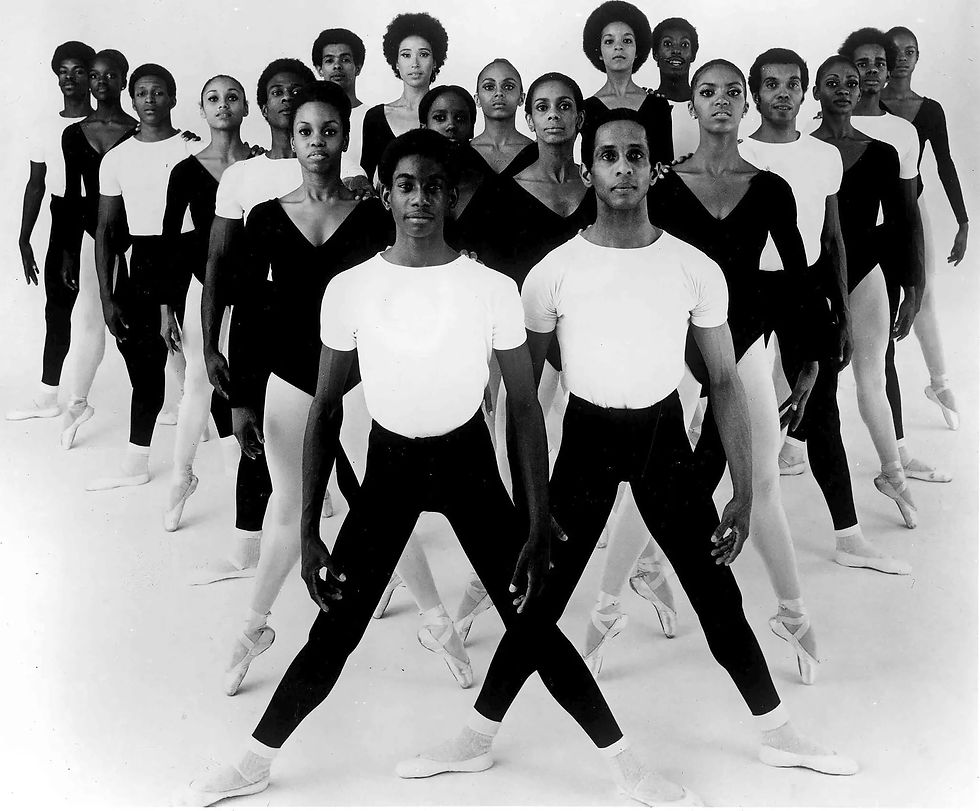

After becoming the first Black principal dancer at New York City Ballet, Arthur Mitchell recognized that individual success was not enough. In 1969, he founded Dance Theatre of Harlem, creating a rigorous classical home where Black dancers could train, perform, and be seen as complete artists. It was not an alternative to ballet. It was ballet.

Debra Austin and Lauren Anderson further challenged assumptions about leadership and visibility, proving that Black excellence could not be contained to the margins.

In 2015, Misty Copeland became the first Black woman promoted to principal dancer at American Ballet Theatre. Her achievement was historic, but it also exposed how long recognition had been delayed. While she did not begin the story, her visibility ensured Black ballet maintained a public audience.

Black Ballet as Authorship

Black dancers did not simply enter ballet. They expanded it.

Dance Theatre of Harlem’s Creole Giselle reimagined a European romantic classic through a Creole and Caribbean lens, grounding classical technique in diasporic history. It demonstrated that ballet is not culturally owned. It is culturally responsive.

Contemporary Black led companies continued this expansion, blending classical foundations with modern movement, spiritual inquiry, and global musical traditions.

Though it has often been claimed that Black artists diluted ballet, the truth is they deepened it. Their bodies did not weaken the form’s lines. They expanded its language. Their presence challenged narrow ideals of beauty and returned ballet to its original purpose: communicating humanity, not uniformity.

The Ongoing Erasure

Today, Black ballet history is often reduced to milestones. The first. The breakthrough. The headline moment. While these achievements matter, they frequently flatten deeper stories, muting recognition of the sustained Black contributions that shaped both ballet’s past and present.

Many Black ballerinas trained extensively, toured internationally, mentored younger dancers, and shaped companies without becoming household names. Their legacies persist through oral history, community archives, and intentional remembrance rather than institutional preservation.

Erasure rarely announces itself. More often, it appears as incomplete memory, diminished accounts, and histories quietly redirected rather than fully told.

Fragmented Focus

Ballet now gestures toward progress, yet its attention remains divided. Aesthetic standards rooted in whiteness still define refinement, shaping casting choices, costuming, and technical ideals. Black led institutions continue to face unequal access to funding, touring opportunities, and archival care, while white institutions are treated as default custodians of tradition.

Representation, when it appears, is often isolated. Individual Black dancers are elevated as symbols rather than integrated as contributors within a collective. Alongside visibility comes an unspoken burden: the expectation that Black dancers must represent progress, history, and community simultaneously.

The result is movement without alignment. Ballet advances in fragments rather than cohesion.

Current Black Leads in Classical Ballet

In the present landscape, Black dancers are no longer only pushing at ballet’s edges. Some are holding its center.

Misty Copeland remains one of the most visible classical leads of the modern era. Her principal status at American Ballet Theatre placed a Black woman at the emotional core of roles long treated as unreachable. Her work affirmed authority rather than novelty. She met ballet fully and expanded its imagination.

Alongside her, Calvin Royal III has emerged as a consistent leading man within ABT’s classical repertory. His presence quietly challenges assumptions about who may embody romance, vulnerability, and command on ballet’s most prestigious stages. His performances do not ask for permission. They assume belonging.

Their shared appearances in canonical ballets offered something still rare in classical ballet: Black dancers centered not as symbols of progress, but as protagonists within stories long claimed as universal.

Beyond individual companies, Black dancers continue to appear as leads across regional and international stages, though still unevenly. Visibility has increased. Structural support has not always followed.

An Open Invitation

Over the past 3 decades, Black presence in ballet has become more visible, though still constrained. Barriers have shifted within institutions once thought immovable, allowing Black dancers to lead classical works previously denied to them. These moments matter not because they’re rare, but because they confirm that talent and excellence were never absent, only recognition was.

At the same time, many celebrated contemporary ballets continue to center abstraction and universality, allowing diversity in casting while leaving Black interior life peripheral. Inclusion exists, but intention often lags.

Black choreographers are reshaping repertories. Black led companies continue to build with fewer resources and higher expectations. Ballet now stands at a threshold.

The invitation is open. What remains to be seen is whether the field is willing to move beyond symbolic inclusion toward shared authorship, sustained leadership, and a future expansive enough to hold the fullness of its artists regardless of color and ethnic origin.

Comments