“Don’t Play with Obeah”: Revisiting CaribbeanSpiritual Roots through Obeah’s

- Selina Gellizeau

- 6 days ago

- 12 min read

The Word They Taught Us to Fear

“Don’t play with Obeah.”

These are the warnings echoed through Caribbean homes, across generations that blended

fear and fascination. Behind those warnings lies something deeper: a history of power disguised as danger.

We’ve been told for centuries that Obeah is something to run from. But why have the

descendants of the same ancestors who wielded this spiritual intelligence as their super power, learned to fear our own inheritance?

Obeah is not “dark magic.” It is the Caribbean’s oldest act of self-preservation. A system of

ancestral wisdom demonized through colonial propaganda, feared by those who could never

truly understand it, and forgotten by those it was meant to protect.

The Criminalization of Spirituality

To understand Obeah’s misrepresentation, we must return to the time when European powers

feared more than rebellion. They feared remembrance and revenge.

In 1760, the Jamaican Assembly passed the Obeah Act, declaring it a crime punishable by

flogging or death. That same year, Tacky's Rebellion began. This was proof that these laws

were not about ‘witchcraft’ but about silencing and preventing organized resistance.” Barbados, Trinidad, and Guyana kept similar bans well into the 20th century. Some only repealed in the 2000s.

Obeah carried the potential for organization, unity, and revolt. It was the unseen language of

freedom, used by leaders like Nanny of the Maroons and the warriors of Tacky's Rebellion.

It is no coincidence that this power was outlawed. Colonizers understood that to break the

body, you must first colonize the mind, soul, and spirit.

What most do not realize is that Obeah, like other African-rooted spiritual systems, forms the

foundation of many global religions. From Egypt to Ethiopia, spiritual practices rooted in African cosmology influenced early Christianity and Judaism. But in the process of conquest and conversion, these roots were erased from scripture, replaced by imagery and language that sanctified whiteness and vilified Blackness.

But Obeah wasn’t evil, it was effective. And colonizers aimed to demonize what

they couldn’t destroy.

The Church, The State, and The Shame

“The Bible arrived in one hand and the whip in the other.” - Historian, Sir Hilary Beckle.

When Christianity arrived in the Caribbean, it did not come as faith, it came as colonial

technology. Missionaries were not simply men of God; they were empirical agents who

convinced our ancestors that their spirituality was sin. Their task was to convert the soul so

the body would not rebel.

The Church and the State moved as one body, preaching salvation while tightening chains. As

historian Sir Hilary Beckles points out in Britain’s Black Debt: Reparations for Caribbean

Slavery and Native Genocide (2013), the colonial church did far more than bless the system of

slavery, it helped build it. Beckles and other scholars reveal how religious institutions were

among the first to brand Africans as “less than human,” using theology to justify bondage.

The Church of England itself owned plantations across the Caribbean, where enslaved people

were physically branded with the word “Society” permanently marking them as property of the religious elite. Missionary schools were erected not to educate the free, but to train through religious obedience. Profits from enslaved labor funded the very churches and universities that would later boast of their moral superiority.

Christianity, under colonial rule, became a mirror that showed Black people everything but

themselves. The same scripture that taught love was used to demand submission and

acceptance of inhumane treatment. The same hymns that promised heaven were sung over

fields of torment.

Suddenly, Obeah became wicked and admonishable. The very hands that healed, protected,

and blessed were branded “unclean.” Holiness became associated with whiteness. The divine, once seen in the rivers, trees, and stars, was now confined to colonial churches and English sermons.

British missionary societies such as the London Missionary Society and the Moravians built

schools that banned drumming, herbal practices, and African languages, calling them “pagan.”

Converts were forced to renounce Obeah during baptism. Some even made to burn their

talismans often referred to as “fetish objects” before being deemed “civilized.”

The plan was not to spread holiness but to erase real spiritual community. The 1760

Jamaican Obeah Act, passed in the aftermath of Tacky’s Rebellion, criminalized not only

Obeah practice but any African-derived ritual. At the same time, Anglican and Methodist

churches expanded plantation “chapels” to teach enslaved Africans white-washed Christianity. Colonial sermons declared that “a faithful slave is a Christian slave.”

In the words of Reverend William Knibb, a Baptist missionary who later turned

abolitionist, “To make a (black) Christian, they first make a slave forget.”

That indoctrination still lingers in the pulpits. Many Caribbean people pray to a white

Jesus while fearing their Black grandmother’s prayers. We inherited shame and disguised

it as salvation.

In truth: The colonizers’ greatest spell was convincing the Caribbean that God could

only be white.

And yet, Obeah never died. It lived quietly beneath hymnals and behind closed doors, living on through the prayers of grandmothers who knew that the same herbs condemned in church

could heal a fever better than any scripture ever would.

The Misnamed: Healers & Mystics

Strip away the fear, and Obeah appears as a holistic science of survival. It is herbalism,

divination, and psychological insight intertwined. It is what a mother does when she ties a red

string around her child’s wrist to protect them, or when an elder blesses a new home with water and salt.

Obeah has always belonged to the healers. The women who delivered babies, interpreted

dreams, cured fevers, and spoke the language of nature. They were not witches; they were

early scientists of the spirit.

As colonial pressure grew, Obeah found new disguises. It merged with Catholicism,

Pentecostalism, and folklore to survive. What could not be spoken aloud was preserved through underground practice.

Modern “energy healers” and “manifestation coaches” are practicing sanitized

Obeah. They’ve simply renamed it something white-passing.

Obeah in the Modern Mind

Today, Obeah still sits at the margins of Caribbean identity. Still feared, mocked, and

misunderstood. It is criminalized in some islands, but still whispered about in others. Yet,

paradoxically, we have embraced spirituality imported from everywhere else. We smudge sage, pull tarot cards, and manifest under the moon while laughing at our auntie who practices Obeah.

Obeah has been turned into a punchline, a horror trope, a Halloween costume. The media

shows it as blood spitting and cursing. Never the balance and care it’s intended to. But across

the diaspora, a quiet revival is taking place. Young people are reclaiming herbalism, astrology,

and ancestral practices and traditions. The very thing we were told to fear is being remembered as true medicine of the soul.

If we post moon rituals on Instagram while mocking the women who once held the

real wisdom. Who really needs deliverance?

From Myth to Medicine

To reclaim Obeah is to understand and be aware of its power, not worship it; not wield it

recklessly. Obeah is ancestral technology that makes art of harmonizing the seen and unseen,

of using intuition as intelligence, and energy as medicine.

It is how our ancestors read the wind, listened to the land, and spoke to the spirit world without shame or spectacle. It teaches self-awareness through ritual, accountability through energy, and healing through knowledge of the body and the earth. The Obeah practitioner was the first therapist, midwife, herbalist, and energy worker of the Caribbean. They understood that the body keeps memory, that words can wound or heal, that herbs shift hormones and mood, and that prayer, real prayer, is simply the conscious direction of energy.

Reclaiming Obeah means confronting and dismissing the colonial narrative that reduced it to

mere superstition. It’s returning to self-knowledge. It means remembering that intuition is data,

that emotion is energy, and that our connection to nature is one of our greatest diagnostic tools. It is the act of knowing yourself so deeply that no system, political, medical, or religious can tell you who you are or what you need to heal.

Reclaiming traditional, spiritual practices such as Obeah asks us to question everything we

were taught to fear and to see our ancestral science not as a threat but as a blueprint for

liberation. It invites us to reclaim rituals of protection, rest, and renewal. The ones we still

practice without realizing it. From lighting candles for clarity to bathing with herbs for peace, we are already remembering what it means to create awareness of spirit.

This is what Obeah truly is: a framework for freedom. A reminder that to be well, whole, and

wise is itself a revolutionary act, and that healing, in the truest sense, has always been our

legacy.

Was Obeah really evil, or did it challenge and survive every effort to erase it?

The Return of the Wise

Your spirit was never meant to be controlled.

To reclaim traditional spiritual practices like Obeah is to heal the fracture between fear and faith. It is to understand that divinity is not something we must seek outside ourselves, but something we carry, and can only access from within.

So the next time you hear, “Don’t play with Obeah,” remember this:

They were right.

Don’t play with it.

Respect it.

Because the power they tried to bury still beats inside us.

The Famous Obeah Men and Women: Keepers of Forbidden Spirituality

Behind every revolution, every prayer for protection, and every secret cure passed down

through generations, there were those who carried the weight of Obeah on their backs.

Sometimes at great personal cost.

1. Nanny of the Maroons (Jamaica)

Queen Nanny remains one of the most legendary Obeah women and freedom fighters in

Caribbean history. She was a leader whose spiritual and tactical brilliance reshaped Jamaica’s

fight for liberation.

In the 18th century, she is credited with freeing and protecting more than 1,000 enslaved

Africans, guiding them into the steep, forested terrain of eastern Jamaica where they

established Nanny Town. The autonomous Maroon stronghold hidden deep in the Blue

Mountains that became their safe haven.

Within those mountains, Queen Nanny transformed Obeah into both shield and strategy.

Traditional stories tell of her visions. How she foresaw enemy movements, healed wounded

warriors, and called upon ancestral spirits to fortify her people. The British, with all their

weapons and war plans, never succeeded in capturing her because they could not comprehend the depth of her power or anticipate her next move.

Colonial records, when not destroyed or distorted, acknowledge the British military’s repeated

failures against the Maroons under her command. Her leadership and Obeah-based spiritual

warfare secured autonomy for her people and symbolized the unbroken will of the African spirit.

Today, Queen Nanny is more than a national heroine. She is the living embodiment of

resistance through faith. She is proof that what colonizers called superstition was, in truth,

strategy, protection, and prophecy.

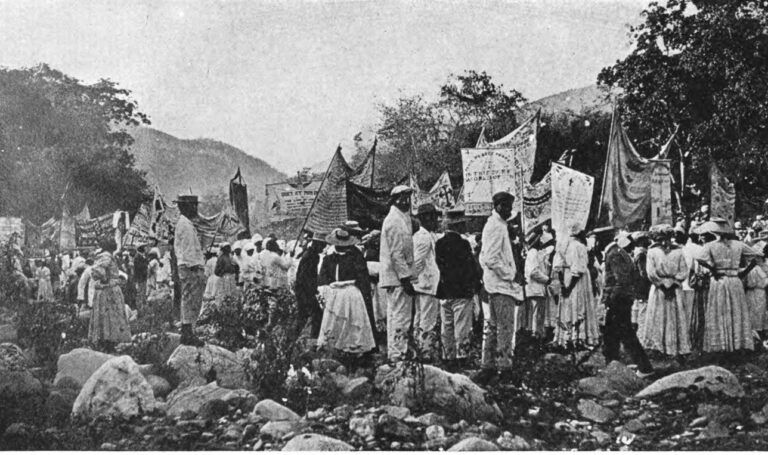

2. Takyi and the Obeah Rebellion (Jamaica, 1760)

Captain Takyi, an Akan chief captured from the Gold Coast and enslaved in Jamaica, became

the leader of one of the island’s most significant uprisings. In 1760, he and a group of trusted

warriors launched a rebellion at Frontier Estate in St. Mary Parish. A revolt that would soon

ignite the entire island.

Historians estimate that several hundred enslaved Africans initially joined Takyi’s cause, with the movement rapidly swelling to over 1,000 participants across St. Mary and St. Thomas

parishes. Guided by Obeah men who fortified their courage with ritual, prophecy, and spiritual

protection, Takyi’s forces reclaimed plantations, seized weapons, and declared themselves Free People. For a brief but powerful moment, hundreds of enslaved people tasted autonomy. It was living proof that freedom was possible.

As the rebellion spread, colonial authorities panicked. When Takyi was eventually captured and executed, the British severed his head and displayed it publicly, hoping fear would silence the uprising. But that message backfired. The story is that his spirit refused to die; his name became a battle cry, in secret by those who continued to resist.

Though the rebellion was ultimately suppressed, dozens were freed in its wake, and

thousands were inspired. Takyi’s defiance helped spark future Maroon alliances and uprisings, ensuring that Obeah would forever be tied to liberation, not fear. The so-called “enchantments” of his followers were not superstition, but strategy. They were spiritual warfare in its purest form.

3. Mother Nanny Grigg (Barbados)

During the 1816 Bussa Rebellion, Nanny Grigg, an enslaved woman and domestic servant, was

said to possess Obeah knowledge that inspired others to rise up. She was executed for “inciting revolt through witchcraft,” proving once again how power in the hands of a Black woman terrified the system built to use, abuse, and contain her.

Mother Nanny Grigg’s name is often overshadowed by the more famous Bussa, yet her

influence in the 1816 Barbados Rebellion was both spiritual and catalytic. An enslaved

domestic servant on Simmons Plantation, she was known among her peers for her sharp

intellect and her deep understanding of Obeah. A knowledge that earned her both reverence

and risk.

At a time when enslaved Bajans (Barbadians) were forbidden to gather or ever speak of

freedom, Nanny Grigg used her position within the plantation household to pass information,

evoke courage, and quietly organize her people. She told others that the King of England had

granted them emancipation and that the white planters were withholding it. This was a

dangerous claim that ignited righteous fury among the enslaved population.

Her reputation for “holding spiritual power” made her both respected and feared; colonial

records describe her as a “notorious Obeah woman,” a label used to criminalize her wisdom and leadership. When the rebellion erupted on Easter Sunday, hundreds joined the uprising across dozens of plantations; many inspired by Nanny Grigg’s conviction that divine justice was on their side.

After the revolt was suppressed, she was captured and executed for “inciting rebellion through witchcraft.” Her death was intended to make an example of her, but instead,again, it

immortalized her. Nanny Grigg became a symbol of the dangerous brilliance of Black women

who dared to think freely, speak boldly, and believe that freedom was not a gift but a birthright.

4. Marie Laveau (New Orleans, Louisiana)

Though her legacy is rooted in New Orleans, Marie Laveau’s influence flows through the same ancestral current as Obeah. Traveled from West Africa through the Caribbean and into the American South. Born a free woman of color in 1801, she rose to become the most powerful Vodou Priestess in the city’s history, seamlessly combining African, Catholic, and Caribbean spiritual practices into a system of faith and influence.

Laveau’s power was not confined to the altar; it reached into politics, policing, and public life.

She offered healing, counsel, and protection to both the enslaved and the elite and in doing so, became an underground broker of social power in a heavily segregated world. Those who

dismissed her as a “sorceress” or “witch” misunderstood what she truly represented: the

endurance of African spiritual science disguised beneath rosaries and prayer candles.

Her rituals, much like Obeah, were not merely acts of faith but acts of resistance. They created spaces of dignity and safety for Black people in a society that intentionally denied both. She used her influence to free prisoners, heal the sick, and gather the forgotten. Proving that true power is not loud or flamboyant; it is deliberate, grounded, and ultimately, sovereign.

Marie Laveau’s life blurred the line between mystic and matriarch. Which reminds

us that African spiritual traditions, whether called Vodou, Obeah, or root work, were

never about fear. They were always about freedom.

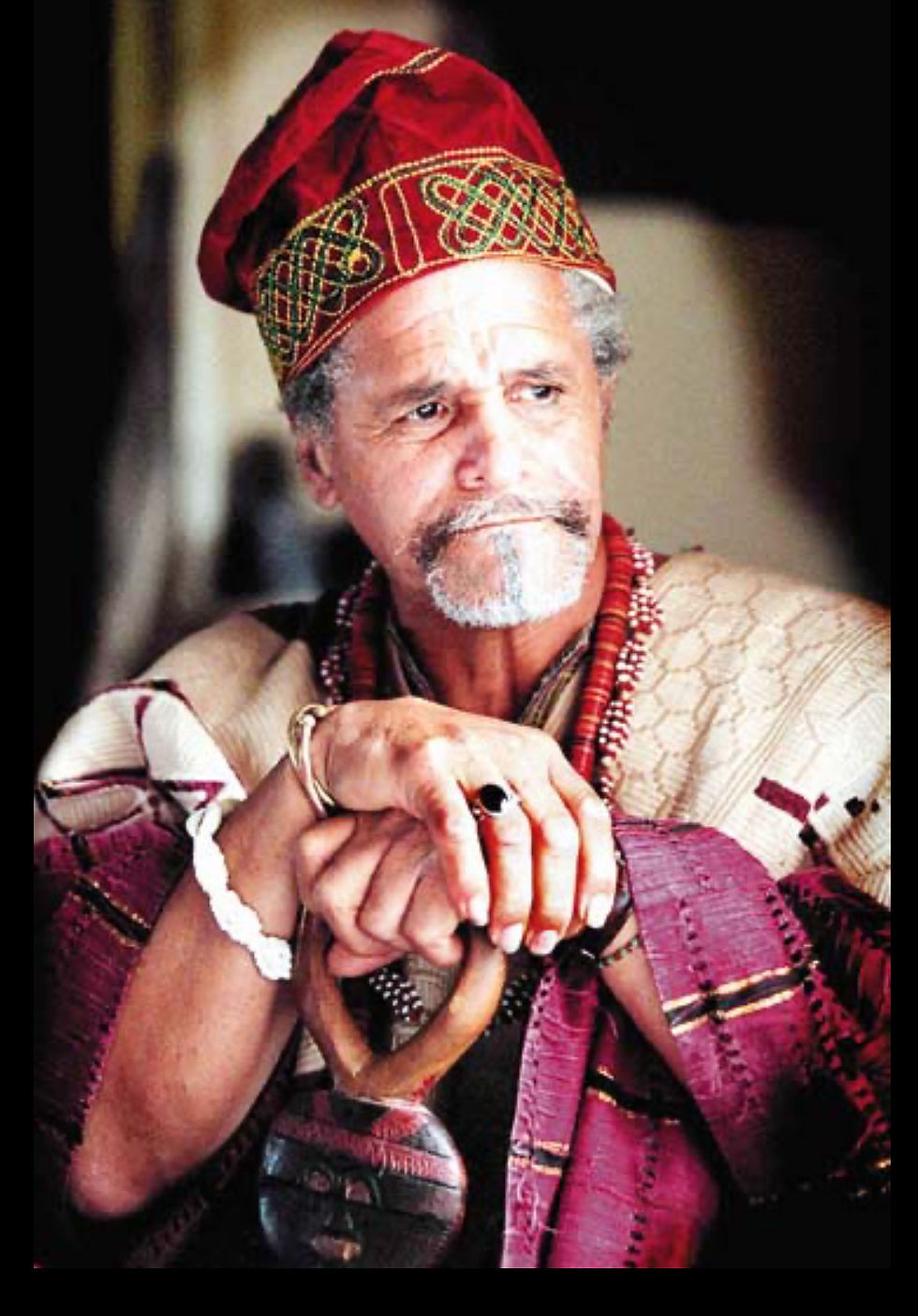

5. Alexander Bedward (Jamaica)

A revivalist preacher from August Town, Bedward’s movement in the late 1800s merged

Christian themes with Obeah mysticism. He was both feared and followed by thousands.

Colonial authorities labeled him insane, a tactic often used to discredit spiritual leaders who

inspired the oppressed.

Alexander Bedward was one of Jamaica’s most enigmatic and misunderstood spiritual leaders. He was a man whose fusion of faith and resistance threatened colonial order as much as it inspired the poor. Born in 1848, Bedward rose from humble beginnings in August Town to become the fiery leader of the Bedwardites, a revivalist movement that blended Christianity with African mysticism and the moral principles of Obeah.

To the colonial authorities, his message was disruptive and dangerous. Bedward preached that Black Jamaicans were divine, that their suffering under white supremacy was not ordained by God, and that spiritual salvation absolutely could not come through the institutions of their oppressors. His sermons drew thousands from across the island, and August Town became a sanctuary for those seeking both healing and liberation.

He baptized in the Hope River, healed the sick, and prophesied the fall of the British Empire.

These acts blurred the lines between religion and rebellion. As his following grew, the

government and church turned against him, labeling him insane and imprisoning him several

times. It was the same colonial tactic used to discredit any Black leader who inspired mass

awakening especially through spirituality.

By the time of his death in 1930, Bedward had become a folk legend. He was revered as part

prophet, part martyr. His teachings helped lay the groundwork for movements like Rastafarism, which would later echo his call for spiritual sovereignty, cultural reclamation and racial pride.

Notable Pattern: When a Black man preached that God looked like the people in

his congregation, the empire called him mad because they knew he was right.

6. The Midwives, The Bush Doctors, The Unnamed

Beyond the famous names were countless unnamed healers. Women and men who kept

communities alive with herbs, prayers, and visions. Their stories were buried under fear and

stigma, but their work lived on and made survival possible.

These were the keepers of everyday Obeah, the ones who carried ancestral knowledge with

them through every struggle, every birth, every breath of resistance that kept their people alive when the world tried to make them forget who they were.

They were the women who delivered babies by moonlight, whispering blessings over the first

breath of life. The men who walked barefoot through the bush, knowing which root cooled fever, which leaf drew poison, and which word could call a restless spirit home. They were healers who served both body and soul, stitching together communities that colonial medicine refused to acknowledge, touch, or approve.

Though their practices were criminalized and their names erased, their knowledge formed the

foundation of Caribbean herbal medicine, folk healing, and even modern wellness traditions.

Every “old-time remedy,” every bottle of bush tea or protective charm, carries the trace of their wisdom and the fragments of a science passed hand to hand, heart to heart.

Comments