Where the Ancestors Gathered: The Secret World of Gullah Praise Houses

- Nicole Simone

- Feb 9

- 4 min read

Spiritual Sanctuary, Silent Strategy, and the Living Legacy of Gullah Worship

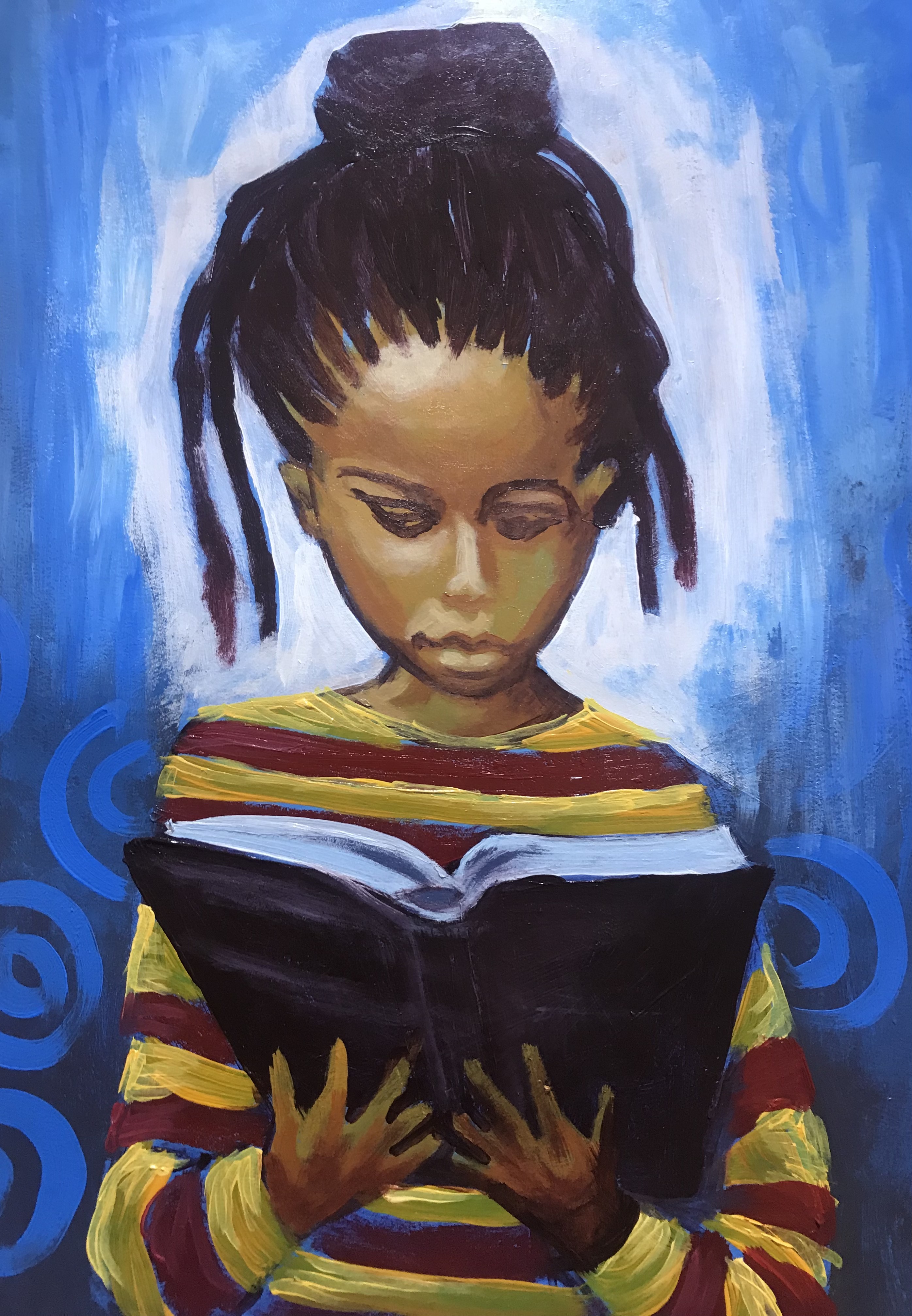

The night was thick with humidity and the distant call of cicadas as a small group gathered quietly beneath the veil of darkness. Lanterns cast flickering shadows on the rough wooden walls of a humble praise house nestled among the marsh grasses. Inside, voices whispered prayers and songs, weaving a tapestry of hope and resistance. The air pulsed with the rhythm of feet shuffling in a sacred circle, hands clapping in time, and the low hum of voices lifted in a secret hymn.

To the unknowing eye, it was nothing more than a rough-hewn chapel—bare walls, a dirt floor, benches fashioned from planks. But to those who entered, it was a portal: a place where the enslaved could whisper to their ancestors, sing their grief into hope, and dream of freedom.

These were the praise houses of the Gullah people, scattered across the Sea Islands and Lowcountry plantations of South Carolina and Georgia. They were modest in size, but immense in meaning.

A World Within Four Walls

The praise house was never grand. It didn’t need to be. Its power came not from stained glass or steeples, but from the voices that filled it. The sound of feet shuffling in a circle, the rise and fall of call-and-response, the thunder of hands clapping in rhythm—these were the instruments of worship.

Here, Christianity mingled with African memory. The ring shout, a sacred dance carried from West Africa, circled the room like a heartbeat. Songs like “Steal Away” or “Go Down, Moses” carried double meanings: prayers to God, yes, but also coded messages of escape and resistance.

Sanctuary and Strategy

Enslavers tolerated praise houses because they seemed to keep people “contained.” But within those walls, containment gave way to community. The praise house was a sanctuary where enslaved men and women could speak freely, if only for a few hours.

It was also a place of strategy. Oral histories tell us that whispers of rebellion, plans for escape, and news of uprisings elsewhere passed from mouth to ear in the shadows of these gatherings. Freedom was plotted in the same breath as prayer.

Two notable historical rebellions linked to this spirit of resistance include the Ebo Landing Rebellion of 1803 in Glynn County and the Boggy Swamp Plantation Rebellion of 1840. The Ebo Landing Rebellion involved a group of Igbo captives who, upon arrival, chose to resist enslavement by walking into the water, symbolically reclaiming their freedom through death rather than submission. The Boggy Swamp Plantation Rebellion was a significant uprising where enslaved people organized a revolt against brutal plantation conditions, demonstrating the courage and resilience that praise houses helped nurture. The plantation owner was beaten to death with hoes by five of his slaves in a cornfield on Boggy Swamp Plantation. The slaves involved in the rebellion and/or tried to escape were Lewis, Little Joe, Ned, March, Joe, Amos, William, and Prince. The escaped Lewis, Little Joe, Ned, and Prince tried to flee to Savannah but were captured, tried, and convicted. William, Big Joe, and Amos were found not guilty, while the others faced the gallows. They were hanged near the very spot where the plantation owner met his end—a grim landmark now known as The Gallows. Yet, even in this harsh judgment, their defiance echoed a powerful truth: that the fight for freedom, though met with brutal reprisal, was an unyielding testament to their courage and humanity. Their sacrifice became a haunting call for redemption, a reminder that the spirit of resistance could never be extinguished, and that justice, though delayed, would one day find its way.

The Sea Islands: A Cultural Stronghold

The isolation of the Sea Islands created a paradox. Cut off from the mainland, enslaved Africans here endured brutal labor on rice and cotton plantations. Yet that very isolation allowed them to preserve more of their African heritage than almost anywhere else in America.

The Gullah language, a creole blending English with African tongues, a beautifully devised communication among people from diverse linguistic backgrounds, blending elements of English with various West and Central African languages, such as Mende, Vai, Wolof, Igbo, and Yoruba. The isolation of the Gullah community allowed these linguistic patterns to survive, evolve, and thrived in the face of adversity, resulting in a unique language that reflects both African heritage and the forced English influences.

The Gullah language is more than just a means of communication; its shown as centuries of a living link to the Gullah Geechee culture, which is rich in traditions, music, and storytelling. Gullah is preserved in songs, stories, and everyday life, making it an essential part of the community's identity.

So did foodways, crafts, and spiritual practices. And at the center of it all stood the praise house—a place where culture was not only preserved but renewed.

After Emancipation

When freedom finally came, the praise house did not vanish. It evolved. Freed people used them as meeting halls, schools, and centers of self-governance. On St. Helena Island, for example, praise houses became the backbone of community life, where disputes were settled and collective decisions made.

Echoes That Remain

Today, only a handful of praise houses survive, weathered by time but still standing. Step inside one, and you can almost hear the echoes: the stomp of feet, the murmur of prayer, the hushed urgency of voices daring to imagine freedom.

They remind us that resistance does not always roar. Sometimes it whispers in the night, in a wooden room by the marsh, where spirits and ancestors gather, and where the dream of liberation takes root.

Comments